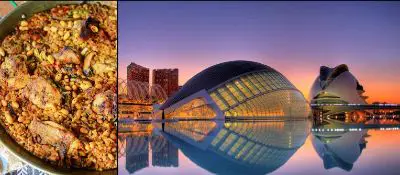

Paella, like all dishes, has an origin. Normally the origin of a dish is not important but in the case of cult dishes like paella it matters a lot. In fact, the history of a dish is part of it and when we talk about non-native dishes, it is important to know where it comes from and what it represents to fully enjoy what we are eating. Here we will tell you everything

Paella Origin

The paella history started in Valencia, (east coast of Spain) making us, its inhabitants, very proud of it. This is the history of Paella Valenciana per se.

Its history arises in modest and rural areas of the Valencia area but is something adopted all around the whole region, currently known Valencian community.

Then, the paella country of origin is Spain.

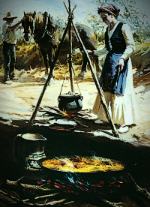

It happened around the sixteenth centuries, by the need of peasants and shepherds for an easy-to-prepare meal. And of course, with the ingredients they could find in their fields.

Curiously, they used to eat it in the afternoon, unlike nowadays where it is only eaten for lunch.

Originally, this quite ancient dish contained as ingredients:

- rabbits or hare

- fowls

- fresh vegetables

- rice

- saffron

- olive oil

Everything was mixed in the pan with the water, so it was meat paella. Do you know the Authentic Meat Paella Recipe?

All together but gradually, it was cooked slowly in a pan directly on a fire carried out with wood from orange trees, that in the meantime add flavor and a characteristic scent.

Paella History

I extracted the following text, translated, adapted and improved from the Spanish website wikipaella. I found it almost perfect.

1238

Jaime El Conquistador liberated Valencia. Rice was already present and cultivated around a lagoon at the gates of the city. This one, behind the coastal cordon, was going to be filled by the peasants and transformed mostly in rice fields.

Jaume I, ordered to move the cultivation of rice away from outside the city walls of Valencia. The reason was it generated an unhealthy environment and a source of disease. (Later other royal edicts would take the rice fields further away from the Albufera).

Then, it became a custom to prepare rice dishes in clay dishes during family and religious festivals. These rituals had a very strong traditional and symbolic character. It is in this period that rice is very successful in the city, it represented an excessively profitable trade.

1324

Llibre de (book from) Sent Sovi; there is only one reference to a recipe for rice (flour) and almond milk.

1520

The first written recipes found are in the Llibre de Coch:

- Arròs ab brou de carn (Rice with meat stock)

- Arròs en cassola al forn (Rice in a casserole in the oven)

“E quant sia acabat de coure veuras que lo arros haura feta vna crosta la qual es molt bona“. Meaning: when you finish cooking you will see that the rice has made a very good crust.

Llibre de Coch

We know that one of its ingredients was fresh eggs, so we deduce that we may find ourselves in front of the rice with crust that they enjoyed in the first representation of Misteri D’Elx.

The “Libre del Coch” by Ruperto de Nola, cook of King Ferdinand of Naples, was the first printed recipe book. It explains how to cut the meat, serve the drink or how to prepare the Mediterranean fish. It is one of the most influential manuals in the history of European gastronomy.

During the reign of Philip II (1527-1598) an embassy of imperial Japan, on his arrival in Spain spent the night in Alicante. Then, everyone was entertained by the local nobility, where they tasted Valencian rice.

Francisco Martínez Montiño, the king’s chief cook, explained all of this in order to make his journey to the Escorial more pleasant.

Sixteenth-century

There is news of the cultivation of rice in Valencia by a study called “General Agriculture” by Gabriel Alonso de Herrera (1470-1539). This book was published in 1513, whose version corrected by the Economic Society Matritense returns to appear in 1818.

In this work, Francisco de Paula Martí y Mora (1761-1827) An eminent scholar of Xàtiva writes a small annex, it is the first relevant text about the use and consumption of rice in Valencia. A crucial documentation to know how rice is cooked in Valencia, unlike the rest of the world.

Here lies the key to why we are so demanding when faced with rice. We are almost two hundred years apart, but little has changed. We transcribe the full text because of its interest to the reader:

Description of Valencian People and Paella

The Valencians have the vanity, in my opinion well-founded, that no one has come to know how to spice it better than them, nor in more different ways, and it is necessary to give them preference, because with anything that is cooked with meat, fish or legumes alone, it is undoubtedly a tasty bite, and all the better the more substance is added.

There is nothing strange about the fact that the Valencians have reached a degree of perfection in this part, unknown in the other provinces, because it is the almost exclusive food with which they are maintained, particularly the people who do not have great faculties, and they have studied for this reason the means of making the palate more pleasing.

Everywhere they have wanted to imitate them, and for this they usually leave it half cooked, mistakenly calling it Valencian rice, persuaded that those natural eat it almost raw, having observed that the cooked grains were whole and separated in the Valencian stews.

But the mystery of this beautiful result consists only in knowing how to provide the amount of broth or water to the rice that they cook, so that it is well penetrated at the same time as having been consumed. We will give, however, here for the curious the rules that we have observed generally keep.

In order for Valencian rice to come out as those natural ones do, it must be cooked on a very active fire, preferring the flame, so that the boiling does not stop.

In order to know the fixed quantity of broth that is needed, whatever it is that one intends to cook, they generally take the rule of stirring it with a wooden spoon, and before it rests…”.

[Francisco de Paula Martí 1818]

19th Century

This description shows how famous the dish was at the beginning of the 19th century, and how the dish was replicated in other regions. Curiously, the word “Paella” does not appear at all quoted in the text, instead “Arroz a la Valenciana” is mentioned.

However, Richard Ford (1796-1858), an English traveller with culinary curiosities, describes rice as: “sol i separat”. When passing through Valencia describes rice as: “sol i separat” in spite of it, the local chroniclers already begin to mention the dish and to distinguish between Paella and Paelleta.

The Valencian Paella in the first half of the 19th century is the dish par excellence in receptions and celebrations throughout Spain. Recently, the Aragonese writer, Jose María Pisa in his book “Biografía de la paella” Ed. De re Coquinaria (2011), has collected innumerable detailed references in this sense.

Although throughout the work he maintains an obsessive fixation to remove from Paella the surname of Valencian, denying an unquestionable identity. For this reason, his book, in spite of the erudition displayed, lacks rigor about paella origin.

Protocolary Uses of Paella at 19th century

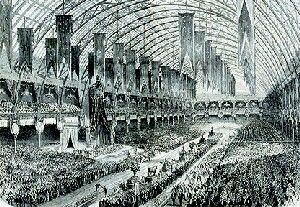

Let’s open a small parenthesis. The character and protocolary uses that the Paella has during the 19th century in Spain, are transferred abroad. During the celebration of Universal Expositions is where Paella or “Arroz a la Valenciana” acquires unusual popularity.

The first of these exhibitions took place in London in 1851 and another in 1862 in the same city. Later, Paris (1867), Philadelphia (1876), Antwerp (1885), Barcelona (1888). These exhibitions served to show the advances of the countries, their natural resources and their incipient industries.

They compared products, disseminated useful ideas and widened the geo-strategic circle in socioeconomic relations. Spain, most of the time, went with Valencian chefs, who offered amazing Paellas, that impressed the audience.

The Valencian region took an active part in this type of event. Then, they organized other regional events, which resulted in the Spanish International Trade Fair.

1867

José de Castro y Serrano, a member of the Royal Spanish Academy and a curious gourmet, stated that one of the restaurants at the Universal Exhibition in Paris served “Valencian Rice”.

The author said: “half of Europe invaded Paris and the other half queued to try it“.

The recipe becomes popular in Belgium where it is called Riz a la Valenciennes and this dish would later become more popular in Brussels (Paella Grand Royale).

1876

King Alfonso XII offers, in solemn banquets, “Arroz a la Valenciana” with this denomination appears in the printed menus of the “ágapes”. The term “Paella” becomes popular years later- to the Prince of Wales and to the Grand Duke of Saxony.

Paella on the King’s table ennobles the dish and favors its spreading. There is evidence, from this moment on, that rice the Valencia way occupies places of honor in numerous celebrations along the Spanish geography.

1885

“Novísimo Manual práctico de cocina española” is published, where there are already clear divergences in the original recipe of the Paella.

1896

The Frenchman, Eugène Lix, films for the first time, the realization of a Paella in Valencia.

The diplomat Ángel Ganivet includes in his “Finnish Letters” the chronicle of a trip to Valencia to eat the “legitimate Paella”. Paella had spread over a much larger territory than the one where it was born. Furthermore, it suffered multiple interpretations and mystifications.

What would make up the genuine Paella that the diplomat was looking for in Valencia? Dionisio Pérez Gutiérrez, author of the first systematic inventory of Spanish regional cuisine, succinctly states: “eels, snails and green beans”.

To the encyclopedic writer and gastronomic chronicler Néstor Luján (1922-1995) this formula seems excessively schematic. Then, he offers data on the presence of chicken or other volatile species, such as wild ducks, at the dawn of the dish.

Paella, at the end of the 19th century, began to evolve in both directions.

A character from Benito Pérez Galdós boasts of having introduced clams in the dish. Besides, and the very ingenious Julio Camba (1882-1962) is skeptical of someone who promotes a Paella with chorizo.

So, at that time, Vicente Blasco Ibañez described the famous specialty of his land as a “great gastronomic circus”.

1906

As part of the International Conference of Algeciras, where the European powers were sourly discussing the future of Morocco. There, the Duke of Almodóvar – head of the Spanish delegation – offered an open-air Paella to the rest of the commissioners.

According to one of the journalists present, after the digestion of the rice, the conflict headed for a quick solution. “A full stomach is a solid guarantee for peace,” concluded the reporter. No one has studied the content of Paella as a diplomatic tool, but someone should because it is a proven fact.

1910

La Paella was experiencing an incredible moment of expansion. It was a dish on the menu served at Delmónico’s Restaurant to which President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) was very fond.

1936-1939

During the Spanish Civil War on the rebellious side, there was an order to shoot the soldiers, regardless of which side they belonged to, if thethe meaning e is paella from?s pay were making an open Paella in the demilitarized zones. The reason was none other than the fidelity shown by Valencia to the Second Republic. It was the last region to surrender.

The influences, comings and goings of the Paella around the world have turned it into a puzzle of gigantic dimensions where there are still many pieces to fit.

Paella boom

Paella became an international dish from the 1960s, when European tourists visited Spain as a developing country that offered all kinds of attractions for the visitor. Spanish gastronomy was one of the keys to success, and paella ceased to be a dish of simple Valencian peasants and became an icon for tourists.

However, its popularity goes beyond its taste, as it has become a symbol of Spanish culture. In this sense, the millions of tourists who visit Spain want to know the famous paella and enjoy it preferably on an outdoor terrace.

Thus, the incipient tourism in Spain offered some attractive ingredients for visitors: good beaches, good parties and good food.

Seafood Paella Origin

The origin of the seafood paella recipe is unknown, but most likely was created later on the coast. The essence was the same, but where other ingredients like fish or seafood more accessible for those who lived near the sea.

Its fame grew throughout the nineteen century in the rest of the country. Then later internationally, becoming today is a dish that can be found almost anywhere in the world.

This notoriety made the dish suffers transformations from the original Authentic Spanish Paella Valenciana (with chicken, duck, rabbit, and snails). After some time, appeared variants making a dish perhaps more sophisticated but not losing neither the base or the essence.